Abstract

Research and writings dedicated to the life of Jackie Robinson have generally focused on his achievements in the realm of baseball. In most of these works, Robinson’s success in breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball is exposed to heighten his contribution to humanity beyond that of a mere athlete. This is not an adequate approach to the study of Robinson’s humanitarian achievements. The focus of this research paper includes and extends beyond baseball to include other aspects of Robinson’s contribution to humanity. It will be shown that Robinson learned at a young age to face adverse situations and fight to create a positive result; a tool he would use throughout his life. Through the utilization of this tool he would be groomed to become the man to break the color barrier in Major-League Baseball. During this period and beyond Robinson’s passion for helping people will be exposed to show his contribution to humanity in the areas of politics, business, civil rights, and charity. The combination of all of these achievements will show that a deeper contribution to humanity was made by Robinson. A contribution beyond that of just baseball which would lead to a legacy that continues to make an impact today.

I. Introduction

Jackie Robinson, who led a full and interesting life, is most well known for his athletic talent. Robinson had many moments of excellence during his life. During each of these moments he endured problematic circumstances. He consistently addressed these problems in a manner that benefited his goals. This resulted in a payoff that not only helped him but also helped those who would follow him. After his baseball career ended, Robinson continued to participate in projects that helped people. After his death, Robinson left a legacy that furthered this commitment to others. Jackie Robinson’s ability to tactfully handle difficult situations and his desire to help others resulted in him making a larger contribution to humanity beyond his extraordinary achievements in baseball.

II. Humble Beginnings

Robinson came from humble beginnings. Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born in Cairo, Georgia, on January 31, 1919. Robinson’s father, Jerry Robinson, was a sharecropper, and the Robinson family lived in a small cottage on the plantation. Jerry had a pattern of deserting his family which left Mallie, Robinson’s mother, heart broken. Mallie and Jerry separated several times during their relationship: “Every patching-up had meant only false hopes and another child.” In 1920, Jerry deserted his family for the final time. At this point Mallie decided to move her family to Pasadena, California on the “freedom train.” The move west represented freedom from the emotionally abusive situation and the chance for a better life.

III. A New Start

The California scenery was a welcomed change for Mallie and her family, but they started out meagerly. Their first residence in California was a small three room apartment near a railroad station. Mallie arrived in her new home financially unprepared to care for her family. She immediately searched for work, which she found in a short period of time. She secured a job as a maid for a white family that ended after her employers moved. However, she soon found work with another white family, the Dodges, whose trust and respect she earned quickly. Twenty years later she was still working for them.” After a few years of saving, Mallie purchased a home on 121 Pepper Street. Their new home was located in an all-white area. The home was secured by the previous African American owners through the use of their real estate agent’s light-skinned niece. Mallie wanted the best for her children and she got it. At that time, Pasadena was ranked as the richest city per capita in America. Being the only African American family in that community, their life was met with daily racial struggles. Robinson learned how to fight early in life due to his mother’s unwillingness to accept abuse as she had in the South:

When Jack was eight years old, he was out sweeping the sidewalk in front of the house one day when the little white girl across the street began to yell ‘Nigger! Nigger! Nigger!’ at him. Jack retaliated by calling her a ‘cracker.’ This brought her father storming out of the house, and he started to throw rocks at Jack. Well, Jack picked up the rocks and threw them right back until the man’s wife finally pulled him inside.

Robinson’s willingness to standup for himself in such situations made life in this all-white neighborhood easier as time passed: “as a teenager, he would band together with other black kids from Pasadena, and they would…play [baseball with] white teams for ice cream and cake.” During this time, Robinson met a man who instilled a strong religious belief that remained with Robinson throughout his life: “their escapades brought…attention. One [of the men] was reverend Karl Downs … who was to become a major influence [as a religious and ethical advisor] in Jack’s life.”

IV. Pasadena Junior College

Things continued to improve for Robinson when he entered Pasadena Junior College (PJC). The exclusion his family initially endured on Pepper Street did not apply at his junior college:

All classes and facilities, including the swimming pool, were open to all students; blacks could attend official school dances without hindrance…On the whole, PJC offered a friendly, relaxed environment, where Jack saw many familiar faces from his earlier schoolboy days.

Robinson arrived at PJC already established as an athlete. Mack, Robinson’s brother, was the premier amateur sprinter of the United States who earned a silver medal competing in the 1936 Olympic Games. Robinson desired stardom and wanted to step out of his brother’s shadow. To do so he decided to play baseball, basketball, and football during his time at PJC. Robinson quickly became a favorite to the baseball teams’ coach. Robinson was always a threat to steal bases, which struck fear into the pitchers of the opposing teams. Robinson became known as a premier shortstop, and he received recognition in the newspaper for “one of the most successful baseball seasons in the history of Pasadena Junior College.” Robinson also established himself as the college’s second best broad jumper. This title of second best was only to his brother, Mack, due to Mack’s extraordinary track and field achievements. Many viewed the brothers as sports rivals, but they did not see it that way: “I had the greatest respect for Mack because of his achievements in track.” Each of their achievements only encouraged each other to do better and reach their full potential: “at PJC, my brother Mack was my greatest fan. He constantly encouraged and advised me. I wanted to win, not only for myself but also because I didn’t want to see Mack disappointed.” Over the summer, Robinson continued to play baseball for a commercially-sponsored team. His base-stealing ability continued to astonish newspaper reporters.

In the fall of 1937, Robinson returned to PJC. That year Robinson focused on honing his football skills. Football was considered the ultimate in college athletics by the PJC community. Robinson secured his position on the team as the quarterback, and his athletic ability was evident on the football field; “Robinson was clearly the most brilliant player on the field.” However, during his first scrimmage he suffered an injury that would keep him off the field for at least a month. The PJC team suffered loss after loss during his absence. After he healed, he returned to the football field and continued to dominate. Robinson finally gained his own recognition due to his athletic talent and the departure of his brother Mack from PJC.

All of the great achievements for Robinson on the field paint a perfect picture; some fans viewed him as college royalty. Even though he was greatly respected for his abilities by PJC faculty and students, he endured struggles during college as he had all of his life. Racial hostility toward Robinson was perpetual during travel to games. He was often excluded from eating with the rest of the team and even from sleeping in the same hotels. This exclusion was enforced by the owners of the establishments in which the team ate and stayed on the road. Robinson was accepted by his team, even praised, but that did not matter to the outside world. In some cases, even new players on his team refused to play with African Americans. However, on the field was a different story. Robinson was a sought-after prospect, and after a conversation with his coach the new players on the team would become exceedingly hospitable. In addition to using his athletic clout, he seized the opportunity to lessen racial oppression on the sports field. Robinson shared his glory with the white players on the team. In return, the new players would block for Robinson harder than ever. Robinson’s decision to share the glory stemmed from “that in the final analysis white people were no worse than Negroes, for we are all afflicted by the same pride, jealousy, envy and ambition.”

All of the great achievements for Robinson on the field paint a perfect picture; some fans viewed him as college royalty. Even though he was greatly respected for his abilities by PJC faculty and students, he endured struggles during college as he had all of his life. Racial hostility toward Robinson was perpetual during travel to games. He was often excluded from eating with the rest of the team and even from sleeping in the same hotels. This exclusion was enforced by the owners of the establishments in which the team ate and stayed on the road. Robinson was accepted by his team, even praised, but that did not matter to the outside world. In some cases, even new players on his team refused to play with African Americans. However, on the field was a different story. Robinson was a sought-after prospect, and after a conversation with his coach the new players on the team would become exceedingly hospitable. In addition to using his athletic clout, he seized the opportunity to lessen racial oppression on the sports field. Robinson shared his glory with the white players on the team. In return, the new players would block for Robinson harder than ever. Robinson’s decision to share the glory stemmed from “that in the final analysis white people were no worse than Negroes, for we are all afflicted by the same pride, jealousy, envy and ambition.”

V. University of California, Los Angeles

After attending Pasadena Junior College, Robinson enrolled in the extension division of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He worked hard and completed the extension requirement which earned him full entry to UCLA in the fall of 1939. Robinson’s reputation as an incredible athlete followed him from PJC to UCLA. However, he worried his coaches after arriving by stating that he was no longer going to strive to be an all-around athlete. His new goal was to compete only in football and the broad jump. Robinson stated, “I think I should study. That is why I chose UCLA. I don’t intend to coast so that I can play ball.” He kept to these promises and focused on his studies. However, his real athletic goal evolved into achieving a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. Although Robinson would never achieve this goal, his athletic ability did not go unnoticed: “At UCLA I became the university’s first four-letter man. I participated in basketball, baseball, football, and track, and received honorable mention in football and basketball.” UCLA was where Robinson really started to get noticed for his baseball ability. His first game was a huge success. One reporter wrote, “the amazing rapidity with which he got his batting and fielding eye speaks well enough for his ability as a baseballer.” Robinson left UCLA before graduating with the excuse of needing to find work to help his mother. However, he was not welcome into the profession that he was most qualified for, which was professional sports. No African Americans were allowed in the National Football League or in Major League Baseball.

VI. Conscription

Robinson would not have to worry about work for too long. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the draft inducted many new recruits. On March 23, 1942, Robinson received his induction notice. Robinson excelled as a soldier, he was declared an expert marksman and he had been noted as having excellent character. Robinson believed these distinctions along with his excellent sports record and his attendance at a four-year college would make him a prime candidate to become an Officer. This goal was not realized in the Army of that time period. He saw many white candidates with lesser ability and credentials accepted into the program, but he soon realized that he was not welcome. The Army denied almost all African Americans the opportunity of becoming officers claiming that: “leadership is not embedded in the Negro race yet and to try to make commissioned officers to lead men into battle-colored men-is only to work a disaster to both.” Robinson was not even accepted on the Army’s baseball team, a position he probably deserved more than most, due to the color of his skin.

Robinson made friends with another tremendous athlete who was enlisted. Joe Louis and Robinson became the best of friend’s right from the start of basic training. Robinson’s friendship helped to break down some of the racial barriers that existed in the Army. One day Robinson shared his situation of not being allowed into Officers school with his friend. Louis called an attorney that he knew. The attorney was the assistant to the African American Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War. This attorney called the Army base to make arrangements to come there and start an investigation. In the end, the Army decided to admit some African American students into the Officers school for the first time in Army history. In 1943, Robinson was a part of that first student body. Robinson’s fight regarding this racial issue marked the starting point for Robinson’s long list of future racial fights. This would help future African American candidates become officers in the Army.

Robinson experienced other racial entanglements in the military which eventually led to his discharge. His discharge involved an incident with a bus driver. Robinson was going to the doctor’s office off the base to have his ankle, an old sports-related injury, examined. When he entered the bus he saw an old friend, Virginia Jones, sitting four rows from the back of the bus and proceed to sit next to her. The bus driver, Milton Renegar, warned Robinson that he would have to move to the back of the bus:

Robinson did not move. He did not incline his head to hear the driver; he did not scowl or stare down at the floor, like an upbraided child. Instead, he stared out of the bus window with sharp and almost theatrical carelessness. A four-letter college athlete from the golden suburbs of Southern California and an officer in the U.S. Army, he was not about to be ordered around by a small town Texas bus driver.

The driver refused to move the bus. Robinson stated that military regulations were clear; he was allowed to sit wherever a seat was available. The military police were summoned at the bus depot and Robinson was taken to be questioned. In the end, Robinson was discharged for being insubordinate, disrespectful, and discourteous.

VII. Kansas City Monarchs

VII. Kansas City Monarchs

After Robinson’s military service ended in November, 1944, he had one prospect for a job. While in the Army, Robinson met another soldier, Ted Alexander, who was a member of the Kansas City Monarchs’ Negro baseball team. This planted the idea in Robinson to join a professional Negro team. He did receive an offer from the Monarchs for $400 a month. The Monarchs were the only Negro team with a white owner, and this gave Robinson a start at the top because the Monarchs enjoyed some privileges that other Negro teams were not able to enjoy. During Robinson’s time in the Negro Leagues he, once again, proved his athletic ability. Some experts claimed Robinson as “perhaps the best curve-ball hitter of his generation.” His fellow teammates were looking to the future and could see Robinson as the one to contest the racial barrier in Major League Baseball. During his time with the Monarchs, he was groomed to be that pioneer. Towards the end of his career with the Monarchs, he was approached by a baseball scout. The scout, Branch Rickey, offered Robinson the opportunity to start playing for Montreal (the Brooklyn Dodger’s farm team) and later, if he could make it, to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. While still playing with the Monarchs he married his long time love Rachael. He would need the love of a good woman to be the first African American to break into the world of white professional baseball.

VIII. Brooklyn Dodgers

Challenge for the newly-married Robinsons’ would start immediately with their journey to Dodger’s camp in Daytona Beach, Florida. They decided to fly, rather than take a train, to the camp on a connecting flight via New Orleans and Pensacola. The couple was excited about the beginning of their new life together, yet apprehensive about the possible first-time encounters with the Jim Crow laws of the South. On February 28, 1946, the couple was sent off by a small group of friends and family at the Lockheed Terminal in Los Angeles. When they arrived in New Orleans, they witnessed Jim Crow signs for the first time in their lives. With an air of defiance, Rachael decided to test the Jim Crow signs in small measure. Walking through the airport she drank from a water fountain marked “White.” To her surprise nothing happened. Then she became a little bolder with her test and entered a Ladies’ Room marked “White.” Again, nothing happed other than a few glaring eyes from the other ladies. Robinson was a little uneasy about her test, but did not try to stop her. Once the time reached the final leg of their flight reality began to set in. They had been notified that there was not enough room on their fight and they would have to be moved to another flight which was scheduled to take off one hour later. When the time came for the next flight, it took off without them and the airline offered no explanation. At this point they were angry. They were getting hungry due to their delayed stay in New Orleans and decided to get something to eat. They soon found out that “Blacks could not eat in the coffee shop.” After an unscheduled twelve-hour delay the Robinson’s were finally admitted on a flight to Florida. When they arrived in Pensacola they were paged to come to the ticket counter. They were notified that they could not continue on the flight for a variety of ridiculous and obviously false reasons. As an alternative, they were forced to take a bus for the rest of their journey, and were forced to sit in the back. All of these trials left Rachael distraught for herself and her husband. She felt that continuing with Branch Rickey’s plan of challenging Jim Crow morality would change Robinson into a submissive man and force both of them to change who they were as people. Arriving on March 2, after thirty-six hours of travel, Robinson was ready to go back to California. His one day late arrival would be explained to the press as “bad flying weather in the vicinity of New Orleans.” In the end, he would decide to stay and become the man to challenge the world of white professional baseball.

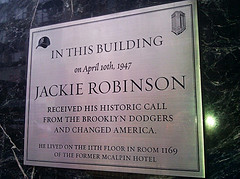

Robinson’s promotion to the Dodgers was met with revolt by certain team members who raised the question of this endeavor succeeding. The opposition mostly came from Southern veterans of the team: Hugh Casey of Georgia, Kirby Higbe of South Carolina, Bobby Bragan and Dixie Walker of Alabama. A few non-southern veterans objected, such as Carl Furillo of Pennsylvania. These team members started a petition in an attempt to keep Robinson off of the team. To end the revolt, Rickey contacted Leo Durocher, the Dodgers’ Manager, and informed him of the petition. Durocher dragged the team out of bed in the middle of the night and stated, “I don’t care if the guy is yellow or black, or if he has stripes like a fuckin’ zebra! I’m the manager of this team, and I say he [Robinson] plays. What’s more, I say he can make us all rich.” Robinson received notice that he was promoted to the Brooklyn Dodger as of April 10 for the 1947 season with a yearly salary of $5,000, the league minimum. Robinson reported to the Dodgers dressing room and was assigned a uniform bearing the number 42. Later in the day he went on to Ebbets Field to meet with the temporary manager, Clyde Sukeforth, to go over the weaknesses of the Yankee team. Sukeforth asked Robinson “how are you feeling today” and when Jackie replied “Okay” Sukeforth continued by saying “then your playing first base for us today [in an exhibition game].” That moment marked the day Robinson would become a certified Major League Baseball player.

On April 15, Robinson set out for Ebbets Field for the season opener against the Boston Braves. This game was not the success that was expected from Robinson, as he recalled, “I did a miserable job.” However, by the end of his first week in the major leagues, his ability became evident. His batting record was six-for-fourteen and he had scored five times. At first base he made thirty-three put-outs without an error. This kind of performance caused game attendance to dramatically increase. He went on to become the Rookie of the Year in 1947. Robinson was met with praise by most fans, even white fans, but he still endured some difficulty. On April 22, 1947 Robinson said, “of all of the unpleasant days in my life, [this day] brought me nearer to cracking up than I ever had been.” On that day he was playing against the Philadelphia Phillies. He could hardly believe the comments he heard from the Phillies dugout which rang in his ear through the entire game:

Hey, nigger, why don’t you go back to the cotton field where you belong?

They’re waiting for you in the jungles, black boy!

Hey, snowflake, which one of those white boys’ wives are you dating tonight?

We don’t want you here, nigger.

Go back to the bushes!

This particular incident was extremely abusive. Robinson was extremely affected because the incident had occurred at home and from a Northern team. He thought to himself:

To hell with Mr. Rickey’s noble experiment…To hell with the image of the patient black freak I was supposed to create. I could throw down my bat, stride over to that Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist. Then I could walk away from it all.

Robinson did not act on his thoughts and remained loyal to the important experiment that he had committed to with Rickey. This incident did provide a chance for him to feel better about the organization in which he was employed. The white Dodger players were extremely angry about the abuse from Ben Chapman, the Phillies manager, and defended Robinson. Later, in the Daily Mirror, Robinson was hailed as “the only gentleman among those involved in the incident” and Rickey commented, “Chapman did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers.”

After the 1947 season, Robinson was the most celebrated African American man in America and became one of the most respected men of any color. His success, even though it was difficult, in entering white baseball yielded a huge financial windfall for the Dodger organization. For him, time was limited, as he was already twenty-eight years old, and he knew that an injury could end his career at any time. He hoped to play professional baseball for up to six more years if he could avoid such an injury. Baseball had become something different to Robinson after breaking the color barrier:

Despite his success, Jack’s interest in playing baseball at his age was limited once the Jim Crow barriers were truly broken. Thereafter, the game was mainly the means to an end, which was twofold: a solid financial foundation for himself and his family, and his long-term desire to help young people, especially the poor and black. He knew that now was the time to make money, while Jackie Robinson was a household name.

He achieved some of his financial goals by endorsing various commercial products and making guest appearances. He also began his quest to help people by doing fund raisers and visiting the sick in hospitals. For Robinson’s efforts on the field, he received a substantial raise in salary with a new total of $12,500 a year.

He achieved some of his financial goals by endorsing various commercial products and making guest appearances. He also began his quest to help people by doing fund raisers and visiting the sick in hospitals. For Robinson’s efforts on the field, he received a substantial raise in salary with a new total of $12,500 a year.

During the 1948 season, Robinson started off slow. He did not start to show his excellence until the middle of June. It was not until his game against Pittsburg that he stole his first base of the season. This game also produced Robinson’s first grand-slam homerun. At the end of the season, the results were the same as his debut season; a huge success. He led the Dodgers in several categories such as batting average, runs batted in, hits, doubles, triples, total bases and runs scored. As a fielder, he was rated the best second baseman in the National League, a position he acquired after the Dodgers previous second baseman was traded.

Robinson received another raise for the 1949 season, and his yearly salary was now up to $17,500. He was eager to prove himself even more this season, especially after the previous season’s slow start. Although he was optimistic about his performance in the beginning of this season, it still took him about a month to warm up and his performance escalated for the rest of the season. This extraordinary performance earned him the honor, with the second most votes behind Ted Williams, of playing in the All-Star Game for this season. Robinson’s game improved so much throughout the season that he was named Most Valuable Player (MVP) of the National League. However, even exceptional playing would not allow the Dodgers to win the World Series that year against the Yankees.

IX. Testifying Before a Congressional Committee

Prior to the All-Star Game, Robinson was called to an endeavor more serious than baseball. Early in July, 1949 he received a telegram from Washington, D.C., which stated that a powerful congressional committee wanted him to come to Washington and testify before it:

On July 8, John S. Wood, a Georgia Democrat, made the request public for Robinson to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC], which he chaired, as it conducted hearings on the issue of black Americans and their loyalty to the nation.

Robinson was unsure about testifying due to conflicting advice from family and friends. However, Branch Rickey strongly advised Robinson to appear. Rickey viewed this as another opportunity to stand up for justice and equality. Robinson received letters and messages from the public and organizations opposing him testifying. Robinson viewed these letters and messages as an attempt to keep him quiet and subsequently made him decide to testify. The committee chairman wanted Robinson to refute statements made by Paul Robeson, one of the most famous African American vocalists and movie stars, concerning African Americans and the Soviet Union. Robeson experienced humiliation during his life because of the color of his skin. However, when Robeson visited the Soviet Union in 1934, he was treated with such kindness that he begun a commitment to radical socialism. The controversy that surrounded this case was a statement Robeson made comparing the United States and the Soviet Union:

It is unthinkable that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country [the Soviet Union] which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind.

This statement was interpreted by many to state that if a war between the United States and the Soviet Union were to happen it would be ironic for African Americans to participate given the history of racism in the United States. This statement placed Robinson in a difficult position by being called to testify, but he felt it was his duty to do so. The difficulty for Robinson was that Robeson was a strong advocate against Jim Crow laws and for the integration of baseball. These were all things Robinson admired Robeson for, but Robinson was also vehemently against Communism. Robinson did his best to be respectful to Robeson while denouncing Communism. Robinson addressed the committee, stating that Robeson had the right to express himself, even if there was nothing to his prediction. Then Robinson stated that most African Americans would act as African Americans had acted in the last war: “They’d do their best to help their country stay out of war; if unsuccessful, they’d do their best to help their country win the war – against Russia or any other enemy that threatened us.” By making these statements, Robinson received praise from African American as well as white community. He successfully denounced Communism while remaining loyal to his own beliefs which coincided with most of the African American community. When Robinson returned from testifying he did not return as just Jackie Robinson the baseball player, but also as a recognized leader of his race.

X. Honors

Robinson was honored by many African American and white organizations during the 1950s. Some of these awards included the gold medal of the George Washington Carver Memorial Institute for being the first African American in Major League Baseball and being honored for his contribution to race relations by the Uptown Chamber of Commerce in Harlem. While Robinson received all of this attention he tried to maintain a sense of balance by stressing his faith in God. He also talked publicly about his baseball career as if it might be close to an end. Even with all of his success, Robinson felt unfulfilled. He felt a need to help the poor and the sick. Robinson wanted to use his new fame and make something political out of it. He wanted to do something that directly addressed social injustice. Robinson became interested in the efforts of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL); in particular the most influential Jewish sector of the organization named B’nai B’rith (Sons of the Covenant). Robinson believed that if black civil rights organizations adopted the techniques that the ADL used to fight anti-Semitism, racial equality would become a reality.

XI. Some Results from the “Noble Experiment”

While Robinson performed brilliantly in the 1950 season, it remained a mild season in terms of controversy. However, the 1951 season gave opportunity for Robinson to show his ability to win the peoples’ admiration. During a Dodgers home game against the Phillies, Robinson was involved in an incident with the Phillies pitcher, Russ Meyer. While Robinson was running from third base, Meyer awaited him covering home plate. This seemed to be an easy out, but Robinson rushed into home plate and Meyer dropped the ball, allowing the score that contributed to the Dodgers’ one-run victory. Meyer had to be restrained from his vicious attack aimed at Robinson. Later, Meyer went to the Dodgers clubhouse to apologize for the incident. Robinson accepted Meyer’s apology and tried to share the blame, “If I hadn’t started down to meet him, there would have been no trouble.” Robinson’s attempt to share the blame in this incident received praise from the public. The Sporting News stated that Robinson was “a player to stir the spirit and admiration of all Americans, who, almost to a man, will respect quality and integrity of performance, allied with seemly deportment.” By the close of the 1951 season, the Major Leagues had a total of fourteen African American athletes thanks to the “noble experiment” Rickey had started four years prior and Robinson’s ability to respond to tough situations in a calm manner. It was Robinson’s success and his conduct that was slowly opening doors for these players.

XII. Thinking of the Future

XII. Thinking of the Future

Prior to training camp for the 1952 season, Robinson participated in activities that included his passion to help people and “pointed directly towards his [future] retirement from baseball.” During this time, Robinson signed a contract with the NBC television network making Robinson the network’s Director of Community Activities for New York. This allowed him to supervise the development of youth programs and work with organizations such as the Police Athletic League, the Catholic Youth Organization, the Boy Scouts, and the YMCA. Robinson also battled juvenile delinquency and involved himself with other social service activities. Robinson also entered into another agreement that would satisfy his desire to help people. He entered into a real estate development deal to construct the Jackie Robinson Houses in or around New York City. Robinson hoped to help poor African Americans to find affordable housing during this postwar era. Robinson had dreams beyond baseball and enjoyed being involved in charity work: “I have had to realize that my baseball days will one day be over and, therefore, I’ve been thinking about a new turning point. This [charity work] is it.”

In 1953, Robinson’s interest in civil rights began to grow. Early in 1954, he became chairman of the Commission on Community Organizations of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ). The NCCJ had sixty offices across the United States and was beginning to emphasize racial justice. During 1954, the NCCJ chose Robinson to do a speaking tour across the country. This was an opportunity for him to speak to thousands of people about racial tolerance, religion, education, and family life. They were all issues that were very important to Robinson, and his speeches were memorable and had an impact on his audience. This gave him a satisfaction that was beyond his achievements in baseball.

The 1956 baseball season would be Robinson’s last. He was thirty-seven years old and had made mentions that “[he would] like to manage a ball club.” This dream of being the first African American manager in baseball would never be realized. However, Robinson did go on to other achievements after his baseball career. Robinson lived the rest of his life with a commitment to helping others. He participated in fundraisers and speaking tours for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to advance the fight for desegregation. Robinson became involved with important political leaders in an effort to further the Civil Rights Movement. His position at the Chock Full o’ Nuts Corporation as Director of Personnel gave him direct control over the welfare of the workforce, which consisted of mostly African Americans. In 1964, he opened the Freedom National Bank in Harlem, New York, in an effort to help African Americans. This remained the only minority owned and operated commercial bank in New York State until 1990. Robinson continued his commitment to help people in so many ways that the influence that he had on humanity continued beyond his living days.

Robinson left a legacy that continued to have a great impact on people:

Also, a significant number of organizations, programs, schools, parks, community centers, and other facilities bearing his name [Jackie Robinson] make a special effort … Our family [The Robinson’s] and the Jackie Robinson Foundation concretely perpetuate his memory and the thrust of his life’s work in other ways. For example, as we strengthen young people by providing education and leadership opportunities, we are giving them the tools to remain hopeful and build their self-esteem, as well as the opportunity to lead meaningful lives and give back to others.

Robinson’s efforts and decisions throughout his life and beyond represent the huge contribution he has made to humanity. Although his athletic ability is included in this contribution it is not where it begins or ends.

During Robinson’s baseball career, he began acting on his desire to help other people. However, due to the commitment that was required in Major League Baseball he was unable to do as much as he would have under different circumstances. After his baseball career had ended, Robinson was able to put forth more effort in helping humanity. This concerted effort focused on four categories: Politics, Business, Civil Rights, and Charity. The remainder of Robinson’s life would be devoted to these endeavors. The achievements he made in these areas are arguably as important as his achievement of being the first African American to rise to the ranks of major-league baseball. All of these achievements would create a legacy that would further Robinson’s goals after his passing in 1972.

XIII. Politics

Robinson’s first experience in politics occurred when he was asked to testify during the Paul Robeson case before the House Committee on Un-American Activities during 1949. During Robinson’s testimony he made it abundantly clear, while making his point in regards to Robeson, that he was fully invested in the future of the United States. Robinson would take this investment more seriously after his baseball playing days were over. Robinson drafted and received many correspondences on behalf of the United States government. Many of these correspondences regarded current political issues that would have an impact on the future of the country. Robinson made his position known to the governmental leaders charged with making these important decisions. He also provided his support to the campaigns of candidates who shared his viewpoints.

Vice President Richard M. Nixon was a political leader that Robinson developed a friendly relationship and a political dialogue. Robinson was vehemently against communism and racial inequality. Nixon also seemed to share these views. Robinson interest in Nixon’s position was at its peak when Nixon made a visit to Africa in 1957. Robinson was particularly impressed with statements Nixon made while in Africa. He showed his support in a letter addressed to Vice President Nixon:

… your telling refutation of anti-American charges made by the Communists…It was most reassuring to have you speak out in the heart of Africa so the peoples of that Continent and of the world should know that…we will never be satisfied with the progress we have been making in recent years until the problem is solved and equal opportunity becomes a reality for all Americans…I am sure that in this statement you express the sentiment of the vast majority of the American people who wish to see an end to racial discrimination and segregation. As you indicated, much remains to be done but progress has been made, especially in recent years, and we are confident that this progress will continue at an accelerated pace until this evil is entirely eliminated from American life.

Robinson hoped that he could convince Nixon to be a different kind of American leader, akin to Abraham Lincoln of the previous century. Robinson believed that if a white politician devoted attention to the Civil Rights Movement then the chances of change would improve. Robinson valued Nixon as a governmental contact who could help further his own political goals. In return, Robinson would become a supporter of Nixon in his future political efforts. For example, Robinson voluntarily campaigned for Nixon’s 1960 Presidential race. Robinson’s support for Nixon did not come without repercussions; he was pressured into taking an unpaid leave of absence from Chock Full o’ Nuts and to end his tri-weekly column with the liberal New York Post newspaper.

Robinson hoped that he could convince Nixon to be a different kind of American leader, akin to Abraham Lincoln of the previous century. Robinson believed that if a white politician devoted attention to the Civil Rights Movement then the chances of change would improve. Robinson valued Nixon as a governmental contact who could help further his own political goals. In return, Robinson would become a supporter of Nixon in his future political efforts. For example, Robinson voluntarily campaigned for Nixon’s 1960 Presidential race. Robinson’s support for Nixon did not come without repercussions; he was pressured into taking an unpaid leave of absence from Chock Full o’ Nuts and to end his tri-weekly column with the liberal New York Post newspaper.

Robinson’s access to the U.S. government was increased with every new political contact he made. This would allow his voice to be heard even within the Oval Office. However, even though he had great hope for advancement through his political connections, this would not insure that all of his wishes would come true. In some cases, his advice was definitely heard but not followed. One such case was in August 1957, when Congress and the Eisenhower administration were negotiating the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. Robinson sent a telegram to the White House explaining that he was opposed to the legislation in its current form. He believed that the bill was too weak to be effective in facilitating a true advancement of civil rights. He made it clear that equal rights could wait a little longer until proper legislation was formed. In summation, he encouraged the President to veto the civil rights bill if it was not amended appropriately. However, in the end President Eisenhower signed the bill into law.

Robinson lent support to politicians who shared his views. In some instances this choice served as a benefit for his cause, while in other instances it did not produce the desired result. Robinson was active in the political arena in an effort to advance issues that he thought were best for America and he sought out political relationships to help further those efforts. As with many other endeavors during Robinson’s life he unselfishly used politics to try to make life better for others.

XVI. Business

Robinson participated in several business ventures during his lifetime. He approached his business dealings in the same way he approached other aspects of his life; with the goal of making a meaningful difference in the world to the benefit of others. Even in businesses where Robinson was an employee, such as Chock Full o’ Nuts, his involvement meant more to him than just another job, it was an opportunity to make a positive impact on someone else’s life. In reviewing Robinson’s actions during his lifetime, one would find it difficult to uncover a purely selfish action. Two examples of businesses that Robinson was involved founding were Freedom National Bank and the Jackie Robinson Construction Company. Both of these examples are of businesses that had a higher purpose beyond generating revenue.

On December 21, 1964, Freedom National Bank opened for business in Harlem. Robinson was very interested in the success of the bank. He believed that the success of the bank would secure a foothold in the financial industry for the African American community:

If Freedom National succeeds, it will set an example which will result in new banks all over the country – banks which are color-blind and banks which have as resources not only their reserve funds, but also support of the masses of the Negro people.

Robinson seized every opportunity to tell people about the importance the bank’s role was in an industry with a history of turning away minority clients. The vigorous attention Robinson paid to the welfare of the bank helped him succeed in his goal.

In 1960, there were only 10 black-owned banks in the U.S. with total assets of $58 million. In the decade following, after the creation of Freedom [National Bank], the nation’s largest black-owned bank, the number grew to twenty-five with over $350 million in assets.

Freedom National Bank continued to serve the needs of the African American community for over twenty-five years. Unfortunately the bank became insolvent by 1990 due to the impact that loose governmental restrictions had on the savings and loans industry during the 1980s.

In line with many of his previous endeavors, in 1970 Robinson founded The Jackie Robinson Construction with the intention of helping other people. He saw a need to provide housing for minorities in and around New York City and wanted to help alleviate that need. The Jackie Robinson Construction Corporation was designed to build low-cost housing through the use of private investments and government sources. This corporation is another shining example of Robinson’s motivation to make an impact on the world and everyone in it.

XV. Civil Rights

Robinson was very passionate about the fight for civil rights. He was determined to extend the right of full legal, social, and economic equality to African Americans. The drive to advance this fight is evidenced in many activities that Robinson participated in after his baseball career. Many of these activities were aimed at creating economic equality through projects like Freedom National Bank and the Jackie Robinson Construction Company. However, this desire was present in Robinson at an early age; from throwing rocks at taunting neighbors as a child to his school days where he frequently used his athletic popularity to create a positive social environment. Many of the people closest to him saw him as a civil rights advocate, not just a baseballer:

To the average man in the average American community, Jackie Robinson was just what the sports pages said he was, no more, no less. He was the first Negro to play baseball in the major leagues. Everybody knew that. . . . In remembering him, I tend to de-emphasize him as a ball player and emphasize him as an informal civil rights leader. That’s the part that drops out, that people forget.

In 1957, Robinson became involved in the Fight for Freedom fund raising drive for the NAACP aimed at the goal of ending segregation by January 1, 1963; a date that was chosen to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Robinson gave himself wholeheartedly to this campaign. He went on nationwide tour giving speeches on behalf of the NAACP. He proved himself as a talented and informed orator earning him a position as the main speaker rather than one who just introduces other speakers. Robinson was eager to use his celebrity to help the Civil Rights Movement. He put forth the idea of hosting a one hundred dollar a plate dinner to support the Freedom Fund which produced fifteen hundred guests. He did not limit himself in the fight for the civil rights movement by just supporting the NAACP. He also supported Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his organizations. For example, Robinson supported the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) which had the goal of redeeming the “soul of America” through nonviolent resistance. Robinson’s involvement in the fight towards civil rights increased on January 8, 1958, when he was elected to the Board of Directors for the NAACP. This marked Robinson’s involvement in the modern Civil Rights Movement. After his election he continued touring to increase support and membership for the organization. While trying to increase membership for the NAACP, Robinson’s celebrity did not protect him from the discriminatory ways of the South. Robinson had to worry about the exposure of his motives in the South just as any other African American would have during this time period. Robinson also participated in many marches and picket lines protesting discrimination. In 1963, he organized a march to integrate schools that walked through Washington D.C. He was inspired by the success of this march with nearly ten thousand students and marchers of all races joined together. In 1967, he resigned from the NAACP’s Board of Directors accusing it of being “insensitive to the trends of our times, unresponsive to the needs and aims of the Black masses—especially the young—and more and more they seem to reflect a refined, sophisticated, ‘Yassuh-Mr. Charlie’ point of view.”

XVI. Charity & Legacy

Robinson was heavily involved in charitable causes during his lifetime. He was especially fond of causes that involved creating opportunities for children. One such organization that he supported was the Harlem branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Robinson’s efforts to help children continued after his death through his wife. Rachael Robinson honored her husband’s passing by founding the Jackie Robinson Foundation during 1973.

Robinson was heavily involved in charitable causes during his lifetime. He was especially fond of causes that involved creating opportunities for children. One such organization that he supported was the Harlem branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Robinson’s efforts to help children continued after his death through his wife. Rachael Robinson honored her husband’s passing by founding the Jackie Robinson Foundation during 1973.

The Jackie Robinson Foundation is a not-for-profit national organization. It was founded to commemorate the memory of Jackie Robinson and his achievements. The foundation assists an increasing number of minority children by granting scholarships for higher education. Each Jackie Robinson scholar receives up to seven thousand two hundred dollars a year in financial support. Scholars also become active members in the foundation’s Education and Leadership Development Program. This program is a mentoring program that includes attending workshops, the assignment of a peer and a professional mentor, and placement into summer internships and permanent employment.

The Jackie Robinson Foundation continues to help children today over thirty years after Robinson’s death.

XVII. Conclusion

Robinson had great athletic talent. However, he had many moments of excellence beyond that particular talent. He overcame the problems that resulted from those moments and paved the way for many people. After his major-league career ended he focused his efforts on helping other people by engaging in political, business, civil rights, and charitable endeavors. Robinson made a huge impact on humanity during the entirety of his life. After his passing he left a legacy that would continue to have a positive impact. Although most people remember Robinson as the first African American in white Major League Baseball, he was a man beyond baseball.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Duckett, Alfred. I Never Had It Made. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972.

Nixon, Richard. Letter to Jackie Robinson. 4 November 1960.

Robinson, Rachel. Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996.

Robinson, Sharon. Stealing Home: An Intimate Family Portrait by the Daughter of Jackie Robinson. New York: Harper Collins, 1996.

Robinson, Jackie. Letter to Richard M. Nixon. 19 March 1957.

Robinson, Jackie. Telegram to Dwight Eisenhower. 12 August 1957.

“The Foundation’s Mission,” The Jackie Robinson Foundation, http://www.jackierobinson.org/about/ (Accessed January 31, 2007).

U.S. Congress. House Un-American Activities Committee. “Testimony of Jackie Robinson 18 July 1949.”

Wilkins, Roy. Letter to Jackie Robinson. 8 January 1958.

Secondary Sources:

Falkner, David. Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson, from Baseball to Birmingham. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

McCarroll, Thomas. “Freedom: Not Just Another Bank.” Time Magazine. 26 Nov. 1990. 6 March 2007. <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,971773,00.html>

Rampersad, Arnold. Jackie Robinson: A Biography. New York: Alfed A. Knopf, 1997.

“Robinson’s Fight for Freedom with the NAACP,” Boston Latin School, http://www.learntoquestion.com/seevak/groups/2000/sites/Robinson/NEWVERSION/robNAACP.html (accessed January 31, 2007).

Simon, Scott. Jackie Robinson and the Integration of Baseball. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002.

“Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC),” Stanford University, http://www.stanford.edu/group/King/about_king/encyclopedia/enc_SCLC.htm (accessed January 31, 2007).

Swaine, Rick. The Black Stars Who Made Baseball Whole. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006.

U.S. National Archives & Records Administration, “Teaching with Documents: Beyond the Playing Field – Jackie Robinson, Civil Rights Advocate,” January 31, 2007, http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/jackie-robinson/index.html?template=print.

U.S. National Archives & Records Administration, “Teaching with Documents: Beyond the Playing Field – Jackie Robinson, Civil Rights Advocate,” January 31, 2007, http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/jackie-robinson/nixon-draft.html.

Photo by Paul Lowry

Photo by pvsbond

Photo by pvsbond

Photo by Keith Allison

Photo by ewen and donabel

Photo by Baseball Collection

Photo by Mike Licht, NotionsCapital.com

Photo by Apuch